As I write, there are approximately 80,000 confirmed coronavirus (Covid-19) cases with over 2,600 reported deaths – numbers that are likely to rise even further in the coming weeks. Reporting on the virus is abundant and scary, and the capital markets reacted sharply this week by posting some of the biggest declines seen in years. The S&P 500 fell -3% in a single day of trading, the yield on the 10-year Treasury fell to a record low, and oil prices sank below $50 a barrel.

To many readers, I realize the situation feels dire. Many investors now find themselves in a challenging position: Should you hedge against the risk of further downside, knowing the crisis is likely to get worse before it gets better? Or do you remain patient and avoid the trap of market timing?

Long-time readers know I’ll almost always argue for the latter option. In my view, the current hysteria surrounding the virus outbreak is worse than the outbreak itself, and I believe the economic impact – while not zero – will be less negative than a majority of people expect. While I can’t see into the future, I have seen this movie before.

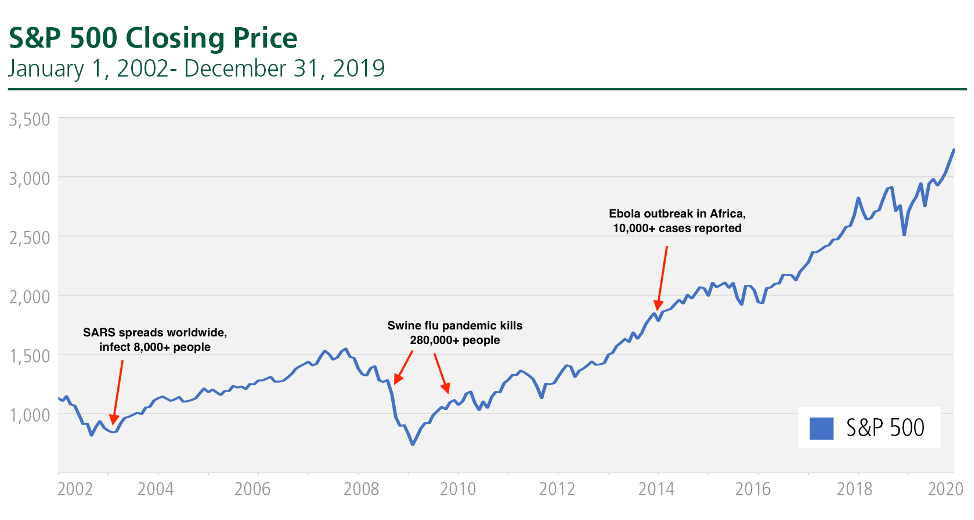

As it stands today, the Covid-19 is worse than Ebola and SARS, which slowed China’s growth materially in 2003. But Covid-19 is still nowhere near the impact of the Swine flu pandemic during 2009 – 2010, which infected somewhere in the neighborhood of 1 billion people, killing over 280,000. By some estimates, nearly 20% of people on the planet were exposed to swine flu at its height.

Source: Zacks Investment Research

As you can see in the chart above, the Swine flu struck at a time when the global economy was in a very fragile state, barely standing on two feet. Consumer and investor confidence were abysmal, and it was difficult for many to see a bright economic future. What happened next, however, was the longest economic expansion and bull market in a century. Virus outbreaks, while scary, have historically been worse on human psychology than the economy.

Another way to frame your thinking on the coronavirus is to simply compare it to the common flu. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that there have been 15 million flu illnesses this season alone, which have led to 14,000 hospitalizations and 8,200 deaths.5 These numbers far outstrip where we are today with Covid-19.

Yes, But Is It Different This Time?

In the very early stages of the outbreak, it is nearly impossible to quantify the economic impact to China, the United States, and the world. We are already starting to see signs that economic output and consumption will feel some significant pressure in China over the short term:

- Tens of millions of people in China are facing lockdowns and restrictions on movement;

- Multiple airlines have suspended flights to mainland China;

- The U.S. issued a “do not travel” to China advisory, a designation generally reserved for the most dangerous situations;

- Apple Inc. and other major corporations have been actively re-routing supply chains outside of China to keep production levels normal;

- Starbucks is warning shareholders of a hit to revenue for the period;

- Major automakers like Ford and Toyota are idling factories for the time being;

- Chinese consumers are staying home.

Many readers might accurately point out that China today makes up a much larger slice of the global economy than it did during the SARS outbreak. China now accounts for approximately 1/6th of total world output, is the world’s largest manufacturer, and Chinese tourists spend approximately $260 billion a year around the world.6 There is little doubt, in my view, that the economic impact to China will be material in Q1 2020 and perhaps even the second quarter. If full containment and eradication takes approximately six months (which history suggests it might), then a slowdown in the world’s second largest economy would almost certainly have rippling effects.

The overarching question for investors, however, is how big those rippling effects might be, and whether or not they lead to a global recession. Again, from where we sit today, this question is near impossible to answer. But the history of past virus outbreaks suggests that virus-related pressures on spending and production are probably not enough to stop an economic expansion in its tracks.

Bottom Line for Investors

As always, when we think about extraneous factors like virus outbreaks, military strikes (like Iran earlier this year), or regulatory forces (like the grounding of Boeing planes), it is important to consider these events in a broader context. In the case of the coronavirus, we can look at SARS, Swine flu, and Ebola – as I’ve done above – to provide information about economic and market impact.

Remember, too, that there have been worse down days for the S&P 500 within this bull market. The market declined more in response to the European Debt Crisis (2011), the Fed “taper tantrum” (2013), the yuan devaluation (2015), and the Brexit referendum (2016).7 Knee-jerk reactions to big, scary headline risks are common in equity markets, but they often don’t last very long. I do not expect the Covid-19 selling pressure will, either.

Investors should also remember that governments and central banks have the means to stimulate the global economy should the crisis drag on. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell signaled that the central bank is watching the situation closely. In the aftermath of the SARS outbreak, factories raised wages to bring workers back and get production moving again. China has already committed massive fiscal stimulus and eased monetary policy. There are tools in the tool shed. However, if the viral outbreak does cause a supply shock, reducing interest rates will likely not be as effective in stimulating the economy as it has been historically.

The overarching question that investors are focused on, however, is how big those rippling effects might be, and whether or not they lead to a global recession. While this is an important question, it is inconsequential to long-term investors. There will be another global recession at some point in time – this is guaranteed. Worrying about whether the next recession will be next week, or next month or next year is immaterial. While recessions will cause stock prices to fall, the long-term value of stocks, which are driven by the present value of future earnings, are for the most part not permanently impacted. The key is to try to avoid heavily indebted companies that may not be able to refinance in periods of economic turmoil and try to give preference towards companies with positive expected earnings. Additionally, the history of past virus outbreaks suggests that virus-related pressures on spending and production are probably not enough to stop an economic expansion in its tracks.

In the meantime, I recommend that investors stay steady, do not let fearful headlines impact their investments and stay focused on the long-term investing approach instead of getting caught up in daily price movements.

Wenn du keinen Beitrag mehr verpassen willst, dann bestell doch einfach den Newsletter! So wirst du jedes Mal informiert, wenn ein neuer Beitrag erscheint!