By Mitch Zacks

22 years ago, James Glassman and Kevin Hassett published a book titled, Dow 36,000: The New Strategy for Profiting from the Coming Rise in the Stock Market. In the book, the two authors claimed the Dow Jones Industrial Average should hit 36,000 almost “immediately,” even though at the time the Dow was trading just above 10,000. It was 1999, however, when euphoric sentiment about stocks was quite common, and many investors thought the market could only go up.

Everyone knows what happened just a year later. The bold, bullish prediction of Dow 36,000 was followed by the tech bubble bursting in 2000. The Dow would not reach the authors’ forecast level until November 2021. The prediction was 20+ years early, and dead wrong.

Glassman and Hassett were not necessarily unqualified to make stock market predictions. Mr. Glassman is a former undersecretary of state and the founding executive director of the George W. Bush Institute, and Mr. Hassett is a former Fed economist who served as Chair of the Trump Administration’s Council of Economic Advisors. Both are well-versed in economic and market matters, but they made an emotionally-charged error forecasting short-term, 100+% gains in a market that was already notably detached from fundamentals.

There are numerous other examples of bold forecasts from credible market and economic experts gone wrong. One is from 1929, when one of the U.S.’s top economists, Irving Fisher, declared that stocks had hit a “permanently high plateau,” implying that the only direction from there was up. Similar to Glassman and Hassett, Mr. Fisher made his prediction at the tail end of the Roaring ‘20s, when positive sentiment was very high. The market began its crash two weeks later, which would eventually give way to the Great Depression.

In 1981, there was a well-known technical analyst named Joe Granville that penned a popular newsletter about stocks and trading. At the beginning of the year, he urged his readers to sell everything, and he remained bearish – incorrectly – throughout the memorable 1980s bull market run. He continued to wrongly refer to the bull market as a “sucker’s rally,” and was never proven right.

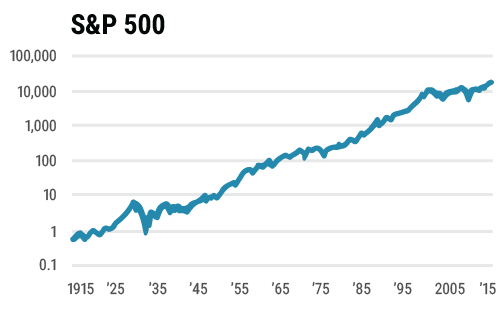

Finally, a more recent example took place in the summer of 2012, when the famed bond manager Bill Gross wrote that “the cult of equity is dying,” and that “investors’ impressions of ‘stocks for the long run’ or any run have mellowed.” This declaration of the death of equities came in the early stages of what might be considered the longest bull market run of history, which is arguably still underway today. Since that forecast was made, the S&P 500 is up well over +200%.

The point of recalling these forecasts is not to admonish the economist or investor who made the prediction. The point is to remind investors that bold market forecasts should be taken with a grain of salt, especially those with set price targets, specific dates, or predictions of massive gains or losses over a short period.

These bold, flashy forecasts often garner the most attention because they are just that – bold and flashy. But believing them can lead to rash and risky decision-making. In 1929, Mr. Fisher borrowed thousands of dollars to make his bullish wager, which ultimately bankrupted him a decade later.

Eine Anlage in den Index S&P 500 hat in hundert Jahren aus einem Dollar 18.000 Dollar gemacht – inklusive Dividenden

Bottom Line for Investors

Investors do not need bold forecasts in order to do well in the stock market and ultimately reach long-term financial goals.

From 1928 to 2020, the average annual geometric return on the S&P 500 was 9.8%. Over the same period, the average geometric return of risk-free 3-month Treasury bills was 3.3%. Comparing the two shows investors the „risk premium,“ which tends to hold across different periods of time and across different countries. Throughout history, it has been reasonable to expect that stocks – over long stretches of time – can generate a 6-7% annualized premium above Treasuries. The effect of this excess return, when compounded, is what leads to wealth generation.

Unfortunately, investors have difficulty staying the course. We know equity markets experience average intra-year corrections of -14.3%, a bear market every few years, and once a decade, investors can expect unbridled white-knuckle panic in the equity markets. Many of these events spook people out of stocks, which compromises the ability to effectively capture the risk premium over time.

Recent history is a great example of the challenges investors face in committing to stocks long-term. In the past 15 years, we’ve experienced the Global Financial Crisis of ’08 and a steep, pandemic-induced bear market. But what is important to realize – which can only really be seen in retrospect – is that the best course of action in a crisis is to buy stocks. It is effectively the Baron Rothschild quote, “Buy when there’s blood in the street, even if the blood is your own.“

For many investors, this mantra is easier said than done, but the takeaway is the same: the history of the United States is the triumph of the optimists, and for investors trying to generate true wealth in the market, the key is to invest and stay invested over long-periods of time, regardless of market fluctuations. The past fifteen years of market returns is a clear vindication of such a strategy.

Wenn du keinen Beitrag mehr verpassen willst, dann bestell doch einfach den Newsletter! So wirst du jedes Mal informiert, wenn ein neuer Beitrag erscheint!